PCjs Machines

Home of the original IBM PC emulator for browsers.

PCjs Blog

Wrapping Up Support for FAT

This will probably be the final post in my “trilogy” of posts about the PC.js command-line utility, now that I’ve (hopefully) finished ironing out most of the wrinkles. I’ve improved FAT12 and FAT16 support, so when pc.js builds either a standard or custom FAT disk image, it should be compatible with whatever version of PC DOS, MS-DOS, or COMPAQ DOS you select.

BTW, there’s no FAT32 support. FAT32 arrived on the scene in 1996, and my focus here at “PCjs HQ” is generally on stuff older than that and/or stuff that personally interests me. So, apologies in advance.

Let’s start with a quick recap of what you can now do with PC.js:

- Start IBM 5150/5160/5170 and COMPAQ DeskPro 386 machines from the command-line

- Start any machine that has a PCjs XML configuration file, like this IBM PC XT or this PDP-11/20

- Boot any version of PC DOS and MS-DOS operating systems

- Build bootable floppy images and hard disk images from any supported version of DOS

- Load any diskette from the large collection of PCjs software diskette images

- Define custom drive types, using any disk geometry the PCjs machine controller will support

- Customize FAT disk images, specifying 12 or 16-bit FAT, cluster size, root directory size, and more

- Seamlessly run local programs (eg,

ls,vi,cp) and access local files from the DOS command prompt - Automatically sync changes between your local file system and the

pc.jsdisk drive

In some ways, pc.js is a culmination of what I started 11 years ago with JavaScript-based machine emulation on the PCjs website (although back then, the website was jsmachines.net; it didn’t become pcjs.org until 2013).

Because I chose to write everything in vanilla JavaScript (sometimes jokingly referred to as Vanilla JS) and not some other language that could be compiled natively and transpiled to JavaScript or WebAssembly, creating a command-line version of PCjs has meant relying on Node.js, and while that works well, it is a rather heavyweight solution.

But I’m OK with that, because PCjs has always been focused on machines from the 1980s and early 1990s, which didn’t run very fast anyway. 16Mhz was pretty respectable back then, and it turns out that JavaScript has no problem simulating that level of performance.

Also, since Node.js, several interesting JavaScript runtime alternatives have popped up, like Deno and Bun. I haven’t tried running pc.js with either of them yet, but I look forward to giving both of them a try. Browsers still rely on JavaScript, and JavaScript doesn’t appear to be going away any time soon.

And JavaScript runtime overhead isn’t actually responsible for the biggest part of PCjs startup time. That honor goes to the PC’s own ROM BIOS “POST” or Power-On Startup Tests – which PCjs faithfully emulates.

Fortunately, there’s a simple work-around for reducing PC startup time: the default machine used by pc.js – a COMPAQ DeskPro 386 – comes with a state file that restores the machine’s state to the point where it’s about to read the boot sector from the machine’s hard disk. So not only are all power-on diagnostics bypassed, but all the floppy drive seek test and boot operations are skipped as well.

Retro Software Development

I really wanted to leverage all the browser-based code I had written over the years to solve a fairly simple problem: compile/assemble/link and run/debug DOS software from a modern non-DOS command-line. In other words, I wanted to integrate a simple retro-software-development environment into my existing macOS dev environment.

And while working on pc.js, I ran into the perfect example. I needed to create my own slightly modified version of the DOS Master Boot Record (MBR), which meant I needed to disassemble an existing MBR, recreate the source as an .ASM file, and then run it through the usual DOS tool chain (masm, link, exe2bin). And it since it would be an iterative process (assemble, test, fix, re-assemble), the easier the process, the better.

Here’s how I was able to do that using pc.js:

In the screen capture above, I start by using my diskimage.js utility to download and extract a complete DOS dev environment from an existing PCjs hard disk image into a directory named test.

Then I cd test and run pc.js, which builds a bootable hard disk image with all the files and folders in test, and then boots it. From that point on, until I run the quit command, I’m running DOS (the default is MS-DOS 3.30). And when I quit, any files that were added/changed/deleted are automatically updated in the local file system.

I can also run a selection of non-DOS commands to access files from the local file system. Every time I type ls or vi, for example, a lot of work happens behind the scenes: the machine is shut down, all file changes are synced, then the non-DOS command is run, and when it exits, the machine’s hard disk is recreated and the machine is restarted.

Booting Different Versions of DOS

The --sys and --ver options control the version of DOS used to the build its bootable hard disk – or bootable floppy disk if you specify --floppy.

By default, pc.js will build a 10Mb hard disk – or the largest floppy disk that your chosen version of DOS supports. If you want something bigger or smaller, use the --target option; it supports either kilobytes (eg, --target=160K) or megabytes (eg, --target=20M).

pc.js will “auto-build” only one disk for a machine: either a single-partition hard disk (C:) or a floppy disk (A:). If you want your machine to automatically load other disks into other drives, you’ll have to create a custom machine configuration file that uses prebuilt disk images.

The whole point of the “auto-build” drive is to mirror the files in your current directory (or whatever directory you specify with --dir). Since you only have one current directory at any point in time, it doesn’t really make sense for pc.js to manage more than one automatically built drive.

However, you can load any diskette image into drive A: or B: at any time using the load command that pc.js includes with every disk image it builds. Details of the load command were covered in an earlier blog post.

Customizing the Drive Type

The IBM PC XT, IBM PC AT, and COMPAQ DeskPro 386 are three examples of machines that supported hard disks, and PCjs includes built-in support for all their respective Hard Drive Types. For example, if you want your machine to be an PC AT with a Type 2 hard disk, run:

% pc.js ibm5170 --drivetype=2

[Press CTRL-D to enter command mode]

C:\>load info

AT drive type 2, CHS 615:4:17, 20.4Mb

16-bit FAT, 2048-byte clusters, 10398 clusters

82 FAT sectors (x2), 64 root sectors (1024 entries)

41752 total sectors, 41523 data sectors, 21295104 data bytes

NOTE: load info is a variation of the load command that displays information about the built-in disk image. I had considered making a separate info utility to do that, since the purpose of the load utility is loading diskette images into drives A: and B:, but I was lazy.

If you don’t remember your favorite PC AT drive type, you can just give pc.js a target size and let it search the machine’s drive table for the closest match:

% pc.js ibm5170 --target=30.6M

warning: 62 FAT sectors allocated, but only 61 are required

[Press CTRL-D to enter command mode]

C:\>load info

AT drive type 3, CHS 615:6:17, 30.6Mb

16-bit FAT, 2048-byte clusters, 15608 clusters

124 FAT sectors (x2), 64 root sectors (1024 entries)

62628 total sectors, 62315 data sectors, 31965184 data bytes

Note that the drive tables of AT-class machines usually didn’t define any drives smaller than 10Mb, and the smallest drive type the PC XT defined was 5Mb, so using --target with smaller sizes won’t give you smaller drives on those machines. To do that, you must bypass the machine’s drive table by adding --controller=pcjs to the command-line. For example:

% pc.js load info --sys=pcdos --ver=3.0 --controller=pcjs --target=1M

[Press CTRL-D to enter command mode]

C>ECHO OFF

PCJS drive type 0, CHS 61:2:17, 1.0Mb

12-bit FAT, 1024-byte clusters, 1012 clusters

3 FAT sectors (x2), 7 root sectors (112 entries)

2040 total sectors, 2026 data sectors, 1036288 data bytes

pc.js will calculate a drive geometry that matches your target size as closely as possible (1Mb in this case), and then set up a custom PCJS drive type.

Finally, for complete control of a custom drive type, you can choose any drive geometry you want by passing a “cylinders:heads:sectors” (CHS) triplet to the --drivetype parameter, and since that automatically uses a PCJS drive type, you don’t need to include --controller=pcjs.

For example:

% pc.js ibm5170 --drivetype=615:5:17

[Press CTRL-D to enter command mode]

C:\>load info

PCJS drive type 0, CHS 615:5:17, 25.5Mb

16-bit FAT, 2048-byte clusters, 13003 clusters

102 FAT sectors (x2), 64 root sectors (1024 entries)

52190 total sectors, 51921 data sectors, 26630144 data bytes

C:\>chkdsk

Volume TEST created Aug 30, 2023 11:10a

26630144 bytes total disk space

90112 bytes in 9 hidden files

45056 bytes in 22 directories

4306944 bytes in 257 user files

22188032 bytes available on disk

655360 bytes total memory

586256 bytes free

Custom drive types work thanks to the Master Boot Record that I created specifically for pc.js. It operates exactly like a normal DOS MBR, with the additional ability to install custom drive tables. And since this is a fully PC-compatible solution, it should work in the “real world” as well – as long as you don’t select a drive geometry that doesn’t work with your actual hardware.

One example of a broken machine/drive combination would be any IBM PC XT machine attempting to boot from a drive using something other than 17 sectors/track. The XT BIOS does support custom drive tables, but that support is hard-coded to disks with only 17 sectors/track.

Customizing FAT Volumes

In the past, PCjs only needed to build a limited number of FAT volume types, so it used a predefined set of BPBs. BPBs (BIOS Parameter Blocks) are data structures introduced by DOS 2.00 and embedded in the DOS boot sector to describe the structure of the disk and the FAT file system on it. For reference, here’s how PCjs defines the BPB (see diskinfo.js):

OPCODE: 0x000, // 1 byte for an x86 JMP opcode, followed by a 1 or 2-byte offset

OEM: 0x003, // 8 bytes (eg, "IBM 2.0")

SECBYTES: 0x00B, // 2 bytes: bytes per sector (eg, 0x200 or 512)

CLUSSECS: 0x00D, // 1 byte: sectors per cluster (eg, 1)

RESSECS: 0x00E, // 2 bytes: reserved sectors; ie, # sectors preceding the first FAT, usually just the boot sector (eg, 1)

FATS: 0x010, // 1 byte: FAT copies (eg, 2)

DIRENTS: 0x011, // 2 bytes: root directory entries (eg, 0x40 or 64)

DISKSECS: 0x013, // 2 bytes: number of sectors (eg, 0x140 or 320); if zero, refer to LARGESECS

MEDIA: 0x015, // 1 byte: media ID (eg, 0xF8); should also match the first byte of the FAT (aka FAT ID)

FATSECS: 0x016, // 2 bytes: sectors per FAT (eg, 1)

TRACKSECS: 0x018, // 2 bytes: sectors per track (eg, 8)

DRIVEHEADS: 0x01A, // 2 bytes: number of heads (eg, 1)

HIDDENSECS: 0x01C, // 2 bytes (DOS 2.x) or 4 bytes (DOS 3.31 and up): number of hidden sectors (0 for non-partitioned media)

BOOTDRIVE: 0x01E, // 1 byte (DOS 2.x): BIOS boot drive # (eg, 0x00 or 0x80)

BOOTHEAD: 0x01F, // 1 byte (DOS 2.x): BIOS boot head # (0-based)

/*

* NOTE: DOS 2.0 also stores the number of sectors in the BIOS file (eg, IO.SYS, IBMBIO.COM) in the byte at offset

* 0x020 (LARGESECS), followed by a custom 11-byte Diskette Parameter Table (DPT) at offsets 0x021 through 0x0x2B, which

* it promptly points the DPT vector 0x1E (0:0078h) to.

*/

LARGESECS: 0x020, // 4 bytes (DOS 3.31 and up): number of sectors if DISKSECS is zero

Most BPB definitions start at offset 0x00B (ie, they don’t include the OPCODE or OEM fields), but I do include them because those fields are actually used by DOS for BPB validation purposes, so their purpose is really inseparable from the rest of the BPB.

My predefined BPBs included all the standard PC floppy disk formats (160K, 180K, 320K, 360K, 720K, 1200K, and 1440K) as well as two hard disk formats (10Mb and 20Mb) – all formats that also used 12-bit FATs.

However, I wanted the pc.js utility to be able to accommodate a much wider range of hard disk formats, along with any version of DOS that supported those formats. This, in turn, meant adding some features I hadn’t needed until now: support for 16-bit FATs (added in DOS 3.00), and support for disks with more than 64K total sectors (added in DOS 3.31).

Neither of those features were difficult to add. Difficulties only arose when actually trying to boot FAT volumes built with custom settings. My troubles started with PC DOS 2.00 – the very first version of DOS to support hard disks – because even though it faithfully places a BPB on every hard disk it formats, it doesn’t actually pay attention to many of the values stored in the BPB.

In PC DOS 2.00, the code that determines a disk’s cluster size and root directory size begins below, where it first scans the MBR for FAT12 partition type 01h. I’ve disassembled and commented the code to make it a bit more readable:

&0070:093B BBC201 MOV BX,01C2 ; BX -> partition record + 4 (it actually starts at 1BEh)

&0070:093E 26803F01 CMP ES:[BX],01 ; is partition type 01h?

&0070:0942 740B JZ 094F ; if so, jump

&0070:0944 83C310 ADD BX,0010 ; otherwise, BX -> next partition record

&0070:0947 81FB0202 CMP BX,0202 ; is BX now beyond the end of the partition table?

&0070:094B 75F1 JNZ 093E ; jump if not

&0070:094D F9 STC ; otherwise, error (partition with type 01h is missing)

&0070:094E C3 RET ;

&0070:094F 268B4704 MOV AX,ES:[BX+04] ; AX = LBA of first partition sector (assumes a 16-bit value)

&0070:0953 894511 MOV [DI+11],AX ; (stash LBA)

&0070:0956 268B4708 MOV AX,ES:[BX+08] ; AX = total sectors in partition (assumes a 16-bit value)

&0070:095A 3D4000 CMP AX,0040 ; is total less than 64 sectors?

&0070:095D 72EE JC 094D ; if so, jump (error)

&0070:095F 894508 MOV [DI+08],AX ; (stash total sectors)

&0070:0962 B90001 MOV CX,0100 ; CH = default sectors/cluster, CL = clusters-to-sectors shift count

&0070:0965 BA4000 MOV DX,0040 ; DX = default number of root directory entries

&0070:0968 3D0002 CMP AX,0200 ; is total sectors <= 512?

&0070:096B 7629 JBE 0996 ; yes (that's only a 256Kb disk)

&0070:096D 02ED ADD CH,CH ; otherwise, default sectors/cluster is now 2 (1K cluster size)

&0070:096F FEC1 INC CL ; shift count to match

&0070:0971 BA7000 MOV DX,0070 ; DX = 70h (112 root directory entries)

&0070:0974 3D0008 CMP AX,0800 ; is total sectors <= 2048?

&0070:0977 761D JBE 0996 ; yes (that's only a 1Mb disk)

&0070:0979 02ED ADD CH,CH ; otherwise, default sectors/cluster is now 4 (2K cluster size)

&0070:097B FEC1 INC CL ; shift count to match

&0070:097D BA0001 MOV DX,0100 ; DX = 100h (256 root directory entries)

&0070:0980 3D0020 CMP AX,2000 ; is total sectors <= 8192?

&0070:0983 7611 JBE 0996 ; yes (that only a 4Mb disk)

&0070:0985 02ED ADD CH,CH ; otherwise, default sectors/cluster is now 8 (4K cluster size)

&0070:0987 FEC1 INC CL ; shift count to match

&0070:0989 03D2 ADD DX,DX ; DX = 200h (512 root directory entries)

&0070:098B 3DA87F CMP AX,7FA8 ; is total sectors <= 32680?

&0070:098E 7606 JBE 0996 ; yes (that's only a 16Mb disk)

&0070:0990 02ED ADD CH,CH ; otherwise, default sectors/cluster is now 16 (8K cluster size)

&0070:0992 FEC1 INC CL ; shift count to match

&0070:0994 03D2 ADD DX,DX ; DX = 400h (1024 root directory entries)

&0070:0996 895506 MOV [DI+06],DX ; (stash defaults in internal structure)

&0070:0999 886D02 MOV [DI+02],CH

So, based solely on total sectors, DOS 2.00 has decided what the cluster size and root directory should be – which means that no matter what values your FAT volume actually uses and has actually stored in the BPB, DOS 2.00 will crash if those values don’t match its defaults. There will be no error message, and unless you have a debugger running, the machine will appear hung.

DOS 2.00 then goes on to calculate how many “sectors per FAT” there should be. It does this by dividing “total sectors” by “sectors per cluster” (which it does by shifting right, since “sectors per cluster” is always a power of 2). That provides an upper limit for total clusters, which it then rounds up to the nearest even number, multiplies by 1.5 (to yield total cluster bytes), and then divides by 512:

&0070:099C 33DB XOR BX,BX

&0070:099E 8ADD MOV BL,CH

&0070:09A0 4B DEC BX

&0070:09A1 03D8 ADD BX,AX

&0070:09A3 D3EB SHR BX,CL

&0070:09A5 43 INC BX

&0070:09A6 80E3FE AND BL,FE

&0070:09A9 8BF3 MOV SI,BX

&0070:09AB D1EB SHR BX,1

&0070:09AD 03DE ADD BX,SI

&0070:09AF 81C3FF01 ADD BX,01FF

&0070:09B3 D0EF SHR BH,1

&0070:09B5 887D0B MOV [DI+0B],BH

This is also one of the many places where DOS also assumes 512-bytes sectors, ignoring the “bytes per sector” field in the BPB.

Since the above calculation of “sectors per FAT” doesn’t take into account any other sector usage (eg, reserved sectors, root directory sectors, not to mention the FAT sectors themselves, of which there are invariably 2 copies), there are going to be situations where DOS allocates more sectors per FAT than the number of available clusters actually requires. And when presented with such a situation, if we don’t over-allocate our FAT as well, DOS 2.00 will again crash – because, in addition to ignoring “bytes per sector”, “sectors per cluster”, and “root directory entries” in the BPB, DOS 2.00 also ignores “sectors per FAT”, relying instead on its own calculation.

To confirm this, I tested a drive configuration (162 cylinders, 4 heads, and 17 sectors/track) which PC DOS 2.00 would format as a 12-bit FAT with 4K clusters, 32 root directory sectors (for a total of 512 entries), and 5 sectors per FAT – yielding a disk with 1361 available clusters. Except that 1361 clusters only requires a 2045-byte FAT, which fits perfectly in 4 sectors, with 3 bytes to spare. However, when I built such a disk with only 4 sectors per FAT, DOS failed to boot.

Here’s how I built it using pc.js:

% pc.js --sys=pcdos --ver=2.00 --drivetype=162:4:17 --trim --save=test.img

The undocumented --trim flag tells pc.js to bypass its normal DOS-compatibility rules and build/format the disk with an “optimized” 12-bit FAT, and the --save option saves the disk image without starting a machine. And although DOS 2.00 didn’t like it, test.img was an otherwise perfectly valid and usable disk image, and fsck_msdos on macOS reported no problems.

It’s understandable that DOS 2.00 would be skeptical of its own BPBs, in part because BPBs were a new feature that probably evolved during the development of DOS 2.00, so they would have been dealing with disks with no BPBs, out-dated BPBs, or even invalid BPBs. However, perhaps the biggest problem was FDISK, because whenever FDISK created a DOS partition, it would simply update the partition table in the Master Boot Record and then reboot, leaving the partition’s boot sector and any BPB it previously contained in place. And that old BPB might be completely inappropriate.

On the other hand, I think DOS 2.00 could have made an effort to validate the BPB, ensuring that its drive parameters matched those in the Master Boot Record before relying on it. But that didn’t happen. To avoid a potential mess, DOS took the easy way out and simply used a set of FAT parameters based entirely on disk size.

Overview of the FAT File System

Before diving into more examples of how picky DOS was about mounting FAT disks, I want to take a step back for a minute and talk about a document that Microsoft first released in the late 1990s called FAT: General Overview of On-Disk Format. The version here (1.03) is from 2000, but as far as FAT12 and FAT16 support is concerned, there are no substantive differences between it and the 1999 (1.02) version. Of course, in typical fashion, Microsoft no longer makes any version of the document available.

Anyway, while working on pc.js, I referred extensively to the FAT12 and FAT16 sections of that document. It reinforced some very important rules, such as:

This is the one and only way that FAT type is determined. There is no such thing as a FAT12 volume that has more than 4084 clusters. There is no such thing as a FAT16 volume that has less than 4085 clusters or more than 65,524 clusters. There is no such thing as a FAT32 volume that has less than 65,525 clusters. If you try to make a FAT volume that violates this rule, Microsoft operating systems will not handle them correctly because they will think the volume has a different type of FAT than what you think it does.

This document was as close to a “gold standard” for the FAT file system as the world ever got – at least from Microsoft. Even so, it does gloss over some important details.

One such detail is when and how a volume should be formatted with FAT12 or FAT16. Actually, let’s break that question into smaller questions:

- When formatting a disk, when should you choose FAT12 or FAT16?

- When formatting a disk with FAT12 or FAT16, how should you select cluster size?

- When mounting a disk, how do you tell whether it’s FAT12 or FAT16?

Regarding question #1, the document does say this:

There is no dynamic computation for FAT12. For the FAT12 formats, all the computation for BPB_SecPerClus and BPB_FATSz16 was worked out by hand on a piece of paper and recorded in the table (being careful of course that the resultant cluster count was always less than 4085). If your media is larger than 4 MB, do not bother with FAT12. Use smaller BPB_SecPerClus values so that the volume will be FAT16.

So that kind of answers the question: maybe use FAT12 if the volume is 4Mb or smaller.

With respect to question #2, there’s no sign of “the table” that DOS used to choose cluster size for FAT12. In DOS 2.00, as we saw above, there was only a series of disk size comparisons, which can be summarized in a table:

Disk Size Cluster Size Root Directory Size

--------- ------------ -------------------

<= 256Kb 1 sector 64 root entries

<= 1Mb 2 sectors 112 root entries

<= 4Mb 4 sectors 256 root entries

<= 16Mb 8 sectors 512 root entries

> 16Mb 16 sectors 1024 root entries

And starting with DOS 3.00, since FAT16 was now preferred, “the table” for FAT12 was reduced to a single entry that always selected 4K clusters and was used only if the disk contained 32680 (0x7FA8) sectors or less (ie, 16340Kb or approximately 16Mb).

As for FAT16 cluster sizes, the document does provide a table:

Disk Size Cluster Size Root Directory Size

---------- ------------ -------------------

<= 4200Kb N/A Use FAT12

<= 16340Kb 2 sectors 512 root entries

<= 128Mb 4 sectors 512 root entries

<= 256Mb 8 sectors 512 root entries

<= 512Mb 16 sectors 512 root entries

<= 1024Mb 32 sectors 512 root entries

<= 2048Mb 64 sectors 512 root entries

And except for the fact that DOS always used FAT12 in the second case as well, that table more or less matches the criteria that DOS eventually used, once disks with those sizes became available.

Note that when DOS 3.00 introduced FAT16 in 1984, the PC BIOS could not support drives with more than 1024 cylinders, 16 heads, and 63 sectors per track, imposing an upper limit of 504Mb. On top of that, DOS versions 2.00 through 3.30 couldn’t support partitions with more 64K sectors, which imposed a volume limit of 32Mb. This is why DOS 3.00 didn’t perform any cluster size calculations: if the disk was big enough to warrant FAT16, then it simply always used 2K clusters. However, as demand for larger disks grew, techniques like CHS translation (that allowed a maximum of 256 logical heads without requiring any changes to the PC BIOS interface) provided support for much larger disks (up to 8192Mb or 8Gb), and then when DOS 3.31 added support for volumes with more than 64K sectors, later versions of DOS had to make more judicious decisions about cluster size.

Question #3 is never really discussed. You might assume the rule is simply that if the partition type in the MBR is 01h, the partition is FAT12, and if it’s 04h (or 06h for disks with more than 64K sectors), the partition is FAT16. But it’s not that simple, and sadly, no one ever thought to add anything to the BPB to clearly indicate the type of FAT – a rather vital piece of information. I’ve learned the hard way that a 10Mb disk formatted with FAT16 and more than 4084 clusters and clearly marked with partition type 04h will still be treated by DOS 3.x as a FAT12 volume by default. More on that later.

Finally, even though Microsoft “sanitized” the document (by which I mean sprinkled a liberal dose of “legalese” and then completely removed any hint of who actually wrote or contributed to it), it’s pretty clear to me who wrote it: Aaron Reynolds.

A Few Words About Aaron Reynolds

I’m sure there are still living current or former Microsoft employees who could easily confirm that Aaron wrote the document, and maybe one will pop out of the woodwork and do just that, but sadly, Aaron isn’t one of them. He passed away in 2008.

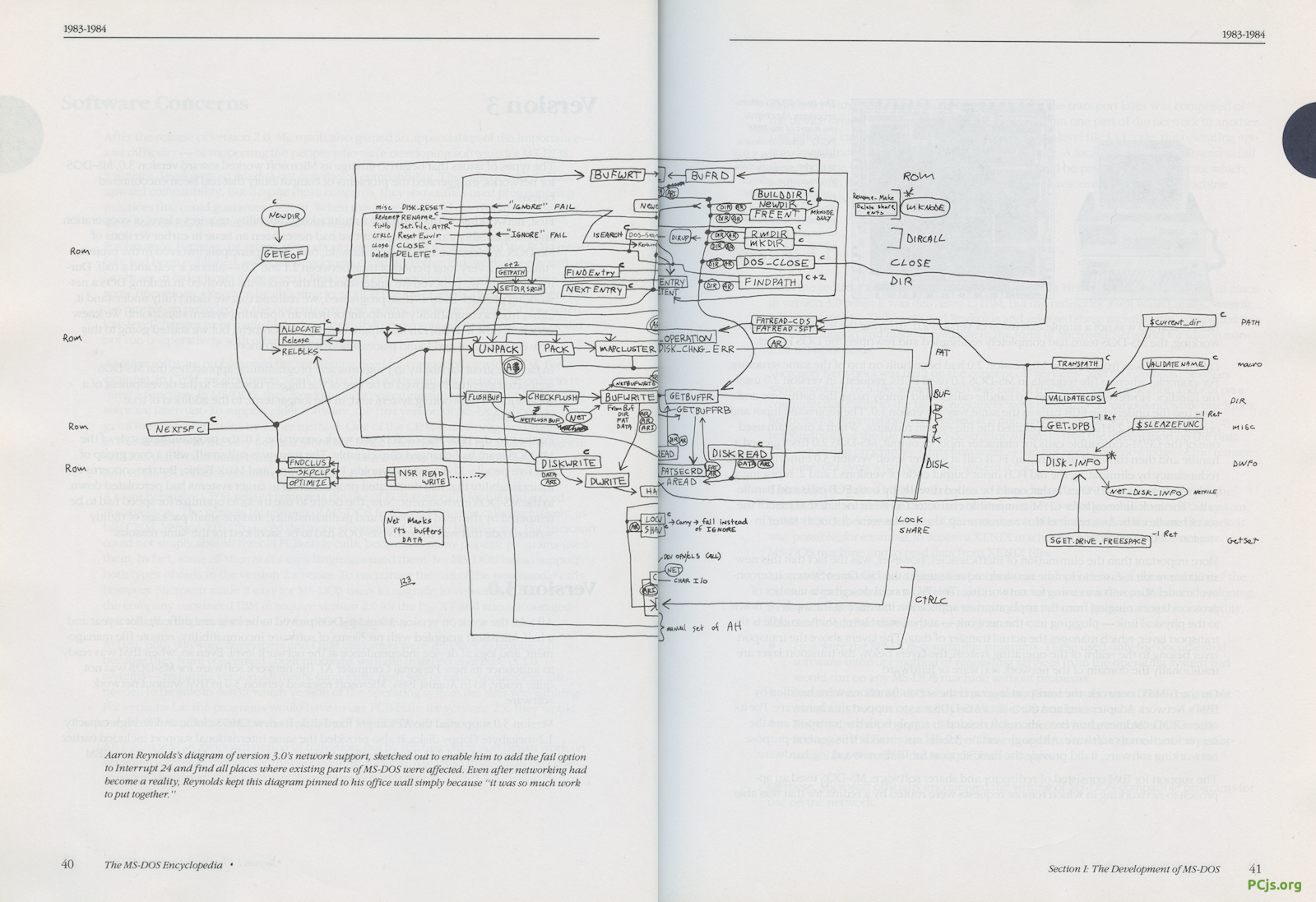

Aaron had a long and legendary career at Microsoft, working on DOS 1.1 and subsequent versions, and well as many versions of Windows. His name appears several times in “The MS-DOS Encyclopedia”, which even includes a hand-drawn diagram by him:

My path occasionally crossed Aaron’s while we were both working on Windows 95, and I even share credit with him on the “Common Name Space For Long And Short Filenames” Patent (No. 5,579,517) – although to be honest, my contribution to that “invention” was pretty minimal. All I recall are hallway conversations about the viability of combinations of attribute bits, including the volume label bit, to hide long filename entries from previous versions of DOS.

Aaron was very smart, opinionated, and intense. One way that intensity came out was a tendency to really “hammer” on certain points, probably because he was tired of seeing other people repeatedly making common mistakes. And there are passages in the FAT: General Overview of On-Disk Format document that strike me as “vintage Aaron Reynolds”.

For example:

There is considerable confusion over exactly how [FAT Type Determination] works, which leads to many “off by 1”, “off by 2”, “off by 10”, and “massively off” errors. It is really quite simple how this works. The FAT type–one of FAT12, FAT16, or FAT32–is determined by the count of clusters on the volume and nothing else.

Please read everything in this section carefully, all of the words are important. For example, note that the statement was “count of clusters.” This is not the same thing as “maximum valid cluster number,” because the first data cluster is 2 and not 0 or 1.

and this:

Now we can determine the FAT type. Please note carefully or you will commit an off-by-one error! In the following example, when it says <, it does not mean <=. Note also that the numbers are correct. The first number for FAT12 is 4085; the second number for FAT16 is 65525. These numbers and the ‘<’ signs are not wrong.

There’s even one paragraph that simply says:

Please don’t draw an incorrect conclusion here.

I can’t read any of those passages without smiling.

There isn’t much about Aaron online, although I did find a nice tribute to him from Charles Wright Academy. I’ll end my own tiny tribute with a short clip of Aaron from July 14, 1995, as he was looking forward to the imminent release of Windows 95 and talking about “harsh email” (I don’t know who taped this, but I’m hopeful they won’t mind it being shared here).

More Fun with DOS and FAT Volumes

I’ve already beaten PC DOS 2.00 to death, so let’s move on to PC DOS 3.00. I’d mentioned this earlier:

A 10Mb disk formatted with FAT16 (ie, with more than 4084 clusters and clearly marked with partition type 04h) will still be treated by DOS 3.x as a FAT12 volume by default.

To test this, I ran pc.js in a directory with a small number of files, requesting a drive with PC DOS 3.00 and a 16-bit FAT:

% pc.js ibm5170 --sys=pcdos --ver=3.00 --fat=16

warning: 16-bit FAT replaced with 12-bit FAT

[Press CTRL-D to enter command mode]

C:\>load info

AT drive type 1, CHS 306:4:17, 10.2Mb

12-bit FAT, 4096-byte clusters, 2586 clusters

8 FAT sectors (x2), 32 root sectors (512 entries)

20740 total sectors, 20691 data sectors, 10592256 data bytes

You can see we successfully booted to a C:\> prompt, but load info told us that the disk was built as FAT12 instead of FAT16. This was because pc.js tries to stick to historical defaults, and 10Mb disks were “historically” formatted as FAT12.

You may recall that the FAT: General Overview of On-Disk Format said:

If your media is larger than 4 MB, do not bother with FAT12.

Except that PC DOS 2.00 did bother with FAT12 on a 10Mb disk – because, well, FAT12 was all it could do. But even when PC DOS 3.00 introduced FAT16, it would still format a 10Mb disk as FAT12. It had to use 4K clusters in order to keep total clusters under 4085, but it preferred FAT12 over 2K clusters – future recommendations notwithstanding.

Anyway, we can force pc.js to build a FAT16 disk. We just have to also specify a cluster size (2K) that will produce too many clusters for FAT12 to handle, forcing the use of FAT16:

% pc.js ibm5170 --sys=pcdos --ver=3.00 --fat=16:2048

[Press CTRL-D to enter command mode]

stopped (32233718 cycles, 4041 ms, 7976669 hz)

AX=0000 BX=FFFF CX=0342 DX=4F03 SP=00C2 BP=0004 SI=FFFF DI=1F64

SS=9E98 DS=0070 ES=9C72 PS=0246 V0 D0 I1 T0 S0 Z1 A0 P1 C0

&017D:4159 0000 ADD [BX+SI],AL

[Type help for list of commands, CTRL-C to terminate]

>> load info

AT drive type 1, CHS 306:4:17, 10.2Mb

16-bit FAT, 2048-byte clusters, 5164 clusters

21 FAT sectors (x2), 32 root sectors (512 entries)

20740 total sectors, 20665 data sectors, 10575872 data bytes

And the machine “crashes” (well, it executes a suspicious instruction at 17D:4159, so the PCjs debugger stops it).

It turns out this happened because I put “IBM 3.0” in the BPB, which seemed logical, since “IBM 2.0” would imply that PC DOS 2.x formatted the disk, but since the disk was using FAT16, it couldn’t have. And yet, ironically, by putting the “old” OEM signature in the BPB, PC DOS 3.00 honors the BPB values, and then later notices that “total clusters” is greater than 4085, so it marks the volume as FAT16 after all, and life is good.

Here’s the code where PC DOS 3.00 inspects the MBR and then the BPB in the boot sector. It appears that the code originally intended to honor a BPB with an “IBM 3.0” signature, but a mistake in the code made that impossible. Again, I’ve sprinkled my own comments throughout the disassembled code to help make it more readable:

&0070:1438 BBC203 MOV BX,03C2 ; BX -> partition table entry + 4

&0070:143B 26803F01 CMP ES:[BX],01 ; type 1? (FAT12)

&0070:143F 7411 JZ 1452 ; yes

&0070:1441 26803F04 CMP ES:[BX],04 ; type 4? (FAT16)

&0070:1445 740B JZ 1452 ; yes

&0070:1447 83C310 ADD BX,0010 ; BX -> next entry

&0070:144A 81FB0204 CMP BX,0402 ; more entries?

&0070:144E 75EB JNZ 143B ; yes

&0070:1450 F9 STC ; no, and we never found an entry, so return error (carry set)

&0070:1451 C3 RET

&0070:1452 52 PUSH DX ; save drive (DL)

&0070:1453 268B4704 MOV AX,ES:[BX+04] ;

&0070:1457 268B5706 MOV DX,ES:[BX+06] ; DX:AX = starting LBA of partition

&0070:145B 26034708 ADD AX,ES:[BX+08] ;

&0070:145F 2613570A ADC DX,ES:[BX+0A] ; DX:AX = ending LBA of partition + 1

&0070:1463 7405 JZ 146A ; are the top 16 bits of the sum zero?

&0070:1465 800ECC1080 OR [10CC],80 ; no, so set 80h in "drive byte" (possible error bit)

&0070:146A 5A POP DX ; recover drive (DL)

&0070:146B 268B4704 MOV AX,ES:[BX+04] ; AX = starting LBA (which we presume to be only 16 bits)

&0070:146F 894511 MOV [DI+11],AX ; stash it

&0070:1472 268B4708 MOV AX,ES:[BX+08] ; AX = total sectors in partition

&0070:1476 3D4000 CMP AX,0040 ; is total less than 64 sectors?

&0070:1479 72D5 JC 1450 ; if so, jump (error)

&0070:147B 894508 MOV [DI+08],AX ; (stash total sectors)

;

; Change from DOS 2.00: Read the partition's boot sector so we can access the BPB.

; What follows is a bunch of instructions that should have been a subroutine (ie, to

; convert the partition's starting LBA to C:H:S values).

;

; Also, it's a bit unfortunate that the volume's boot sector is already sitting in memory.

; Of course, that's only true for the first disk drive, but in the case of the first drive,

; this code is a complete waste of time.

;

&0070:147E 50 PUSH AX

&0070:147F 52 PUSH DX

&0070:1480 8B4511 MOV AX,[DI+11] ; AX = starting LBA again

&0070:1483 33D2 XOR DX,DX ;

&0070:1485 8AFE MOV BH,DH

&0070:1487 8A5D0D MOV BL,[DI+0D] ; BX = sectors per track

&0070:148A F7F3 DIV BX ; divide DX:AX by sectors per track

&0070:148C 8ACA MOV CL,DL

&0070:148E FEC1 INC CL

&0070:1490 99 CWD

&0070:1491 8A5D0F MOV BL,[DI+0F] ; BX = number of heads

&0070:1494 F7F3 DIV BX

&0070:1496 D0CC ROR AH,1

&0070:1498 D0CC ROR AH,1

&0070:149A 80E4C0 AND AH,C0

&0070:149D 0ACC OR CL,AH

&0070:149F 8AE8 MOV CH,AL

&0070:14A1 58 POP AX

&0070:14A2 8AF2 MOV DH,DL

&0070:14A4 8AD0 MOV DL,AL

&0070:14A6 33DB XOR BX,BX

&0070:14A8 B80102 MOV AX,0201

&0070:14AB CD13 INT 13

&0070:14AD 58 POP AX

;

; At this point, the partition's boot sector should be at ES:0 (since BX was zero);

; these instructions could have been a bit smaller if they had used ES:BX addressing.

;

&0070:14AE 26813E03004942 CMP ES:[0003],4249 ; does the OEM signature start with "IB"?

&0070:14B5 751C JNZ 14D3 ; no

&0070:14B7 26813E05004D20 CMP ES:[0005],204D ; does it continue with "M "?

&0070:14BE 7513 JNZ 14D3 ; no

&0070:14C0 26813E0800322E CMP ES:[0008],2E32 ; does it continue with "2."?

&0070:14C7 750A JNZ 14D3 ; no

&0070:14C9 26803E0A0030 CMP ES:[000A],30 ; is the "2." followed by "0"?

&0070:14CF 7505 JNZ 14D6 ; no

&0070:14D1 EB14 JMP 14E7 ; yes

&0070:14D3 EB4C JMP 1521

&0070:14D5 90 NOP

;

; This code is prepared to deal with a signature of "IBM 3.0" and jump to 14E7

; just as previous code did for "IBM 2.0", but technically, that will never happen,

; because previous code already gave up when the signature didn't contain "2.".

;

&0070:14D6 26813E0800332E CMP ES:[0008],2E33

&0070:14DD 75F4 JNZ 14D3

&0070:14DF 26803E0A0030 CMP ES:[000A],30

&0070:14E5 75EC JNZ 14D3

;

; This code is executed ONLY if the OEM signature contained "IBM 2.0"

; (well, technically, the previous code didn't care what came before the "2";

; normally it's a space but it could be anything).

;

; Anyway, this is the only code that actually honors the BPB values.

;

&0070:14E7 26A11300 MOV AX,ES:[0013] ; AX = total sectors

&0070:14EB 48 DEC AX ; subtract 1 (assumes reserved sectors == 1?)

&0070:14EC 268B161600 MOV DX,ES:[0016] ; DX = sectors per FAT

&0070:14F1 89550B MOV [DI+0B],DX ; (stash it)

&0070:14F4 D1E2 SHL DX,1 ; double it (assumes number of FATs == 2?)

&0070:14F6 2BC2 SUB AX,DX ; subtract from total sectors

&0070:14F8 268B161100 MOV DX,ES:[0011] ; DX = number of directory entries

&0070:14FD 895506 MOV [DI+06],DX ; (stash it)

&0070:1500 B104 MOV CL,04 ; CL = shift count

&0070:1502 D3EA SHR DX,CL ; DX /= 16

&0070:1504 2BC2 SUB AX,DX ; subtract from total sectors

&0070:1506 268A0E0D00 MOV CL,ES:[000D] ; CL = sectors per cluster

&0070:150B 884D02 MOV [DI+02],CL ; (stash it)

&0070:150E 33D2 XOR DX,DX ; DX:AX = total sectors

&0070:1510 8AEE MOV CH,DH ; CX = sectors per cluster

&0070:1512 F7F1 DIV CX ; AX = number of whole clusters

&0070:1514 3DF60F CMP AX,0FF6 ; is number of clusters < 4086? (technically, that should be 4085)

&0070:1517 7205 JC 151E ; yes, so it's a FAT12 volume

&0070:1519 800ECC1040 OR [10CC],40 ; no, so mark it as FAT16

&0070:151E EB43 JMP 1563 ; wrap up

&0070:1520 90 NOP

;

; We arrive here if the OEM signature was ANYTHING other than "IBM 2.0".

;

; SI will point to a table of 8-byte entries. There are only two sets of entries.

;

; SI+0: total sectors threshold (1 word) 7FA8 FFFF

; SI+2: sectors per cluster shift count (1 byte) 03 02

; SI+3: sectors per cluster byte count (1 byte) 08 04

; SI+4: root directory entries (1 word) 0200 0200

; SI+6: flags (eg, 0040h implies FAT16) 0000 0040

;

&0070:1521 BEF910 MOV SI,10F9 ; SI -> threshold table

&0070:1524 3B04 CMP AX,[SI] ; AX <= sector threshold?

&0070:1526 7605 JBE 152D ; yes

&0070:1528 83C608 ADD SI,0008 ; no, advance to next entry

&0070:152B EBF7 JMP 1524 ; try again

&0070:152D 8A4C06 MOV CL,[SI+06] ; load flags

&0070:1530 080ECC10 OR [10CC],CL ; save in "drive flags"

&0070:1534 8B4C02 MOV CX,[SI+02] ; CX = sectors per cluster info

&0070:1537 8B5404 MOV DX,[SI+04] ; DX = root directory entries

&0070:153A 895506 MOV [DI+06],DX ; (stash DX: root directory entries)

&0070:153D 886D02 MOV [DI+02],CH ; (stash CH: sectors per cluster byte count)

&0070:1540 F606CC1040 TEST [10CC],40 ; FAT16?

&0070:1545 7525 JNZ 156C ; yes

;

; FAT12 "sectors per FAT" calculation is performed identically to DOS 2.00

; (see the code at 70:099C from DOS 2.00, above)

;

&0070:1547 33DB XOR BX,BX

&0070:1549 8ADD MOV BL,CH

&0070:154B 4B DEC BX

&0070:154C 03D8 ADD BX,AX

&0070:154E D3EB SHR BX,CL

&0070:1550 43 INC BX

&0070:1551 80E3FE AND BL,FE

&0070:1554 8BF3 MOV SI,BX

&0070:1556 D1EB SHR BX,1

&0070:1558 03DE ADD BX,SI

&0070:155A 81C3FF01 ADD BX,01FF

&0070:155E D0EF SHR BH,1

&0070:1560 887D0B MOV [DI+0B],BH

&0070:1563 8A1ECC10 MOV BL,[10CC]

&0070:1567 885D13 MOV [DI+13],BL

&0070:156A F8 CLC

&0070:156B C3 RET

;

; FAT16 calculations (with some duplication of the logic at 70:1500):

;

&0070:156C B104 MOV CL,04 ; CL = shift count

&0070:156E D3EA SHR DX,CL ; DX /= 16

&0070:1570 2BC2 SUB AX,DX ; subtract from total sectors

&0070:1572 48 DEC AX ; subtract 1 (assumes reserved sectors == 1?)

&0070:1573 B302 MOV BL,02

&0070:1575 8A7D02 MOV BH,[DI+02] ; BX = sectors per cluster * 256 + 2

&0070:1578 33D2 XOR DX,DX

&0070:157A 03C3 ADD AX,BX

&0070:157C 83D200 ADC DX,0000 ; DX:AX = sector count + BX

&0070:157F 2D0100 SUB AX,0001

&0070:1582 83DA00 SBB DX,0000 ; DX:AX = sector count + BX - 1

&0070:1585 F7F3 DIV BX ; AX = (sector count + BX - 1) / BX

&0070:1587 89450B MOV [DI+0B],AX

&0070:158A EBD7 JMP 1563

PC DOS 3.00 introduces the same “sectors per FAT” calculation described in the FAT: General Overview of On-Disk Format for FAT16:

RootDirSectors = ((BPB_RootEntCnt * 32) + (BPB_BytsPerSec – 1)) / BPB_BytsPerSec;

TmpVal1 = DskSize – (BPB_ResvdSecCnt + RootDirSectors);

TmpVal2 = (256 * BPB_SecPerClus) + BPB_NumFATs;

FATSz = (TMPVal1 + (TmpVal2 – 1)) / TmpVal2;

The document goes on to say:

Do not spend too much time trying to figure out why this math works. The basis for the computation is complicated; the important point is that this is how Microsoft operating systems do it, and it works. Note, however, that this math does not work perfectly. It will occasionally set a FATSz that is up to 2 sectors too large for FAT16, and occasionally up to 8 sectors too large for FAT32. It will never compute a FATSz value that is too small, however. Because it is OK to have a FATSz that is too large, at the expense of wasting a few sectors, the fact that this computation is surprisingly simple more than makes up for it being off in a safe way in some cases.

However, that formula is actually very similar to how DOS 2.00 calculated sectors per FAT for FAT12 volumes. The similarity is just obscured by how the formula assumes a sector size of 512 to arrive at the 256 multiplier, whereas it did not assume a sector size of 512 at the beginning of the formula (it used BPB_BytsPerSec instead).

Ultimately, “sectors per FAT” has to be derived from “total clusters” divided by “number of cluster entries that fit in one FAT sector” (and noting that there are 256 16-bit entries in one 512-byte sector). The only thing that’s “complicated” about the formula is the rationale for adding BPB_NumFATs (which is invariably 2) to the TmpVal2 divisor; it was probably added as a way of compensating for the FAT sectors themselves, since they are not represented in the total overall sectors in TmpVal1.

Final Thoughts

One final observation I’ll make about the FAT: General Overview of On-Disk Format is that, since it was written many years after the earliest versions of DOS supporting FAT12 and FAT16 hard disks were released, it tended to gloss over details that were probably considered irrelevant at that point.

The OEM signature field in the BPB is a good example. The document really only had this to say about it:

There are many misconceptions about this field. It is only a name string. Microsoft operating systems don’t pay any attention to this field. Some FAT drivers do. This is the reason that the indicated string, “MSWIN4.1”, is the recommended setting, because it is the setting least likely to cause compatibility problems. If you want to put something else in here, that is your option, but the result may be that some FAT drivers might not recognize the volume. Typically this is some indication of what system formatted the volume.

Unfortunately, rather than dispelling misconceptions, the document actually added to them, because as we saw above, beginning with DOS 3.00 and – as far as I know – continuing in every version of DOS since then, the OEM signature played a role, sometimes a vital role, in determining the format of the disk and whether the BPB would be used.

pc.js, and the diskinfo.js module in particular, works hard to make sure the custom disk images it builds will work with the selected version of DOS. But I’m sure there are still combinations of drive geometries, FAT sizes, cluster sizes, DOS versions – and OEM signatures – that I haven’t tested and will fail to boot. Hopefully the volumes themselves, at least, will always be valid.

Fortunately, pc.js makes it easy to debug those situations. Just add --halt to the pc.js command-line and you’ll be dropped into the PCjs debugger before the machine starts booting.

Have fun!

Jeff Parsons

Sep 5, 2023